Abundance of supply of very light crude continues to be a great opportunity for Mediterranean refiners, most notably CPC Blend. This paper explains the market mechanisms that set the prices of CPC Blend.

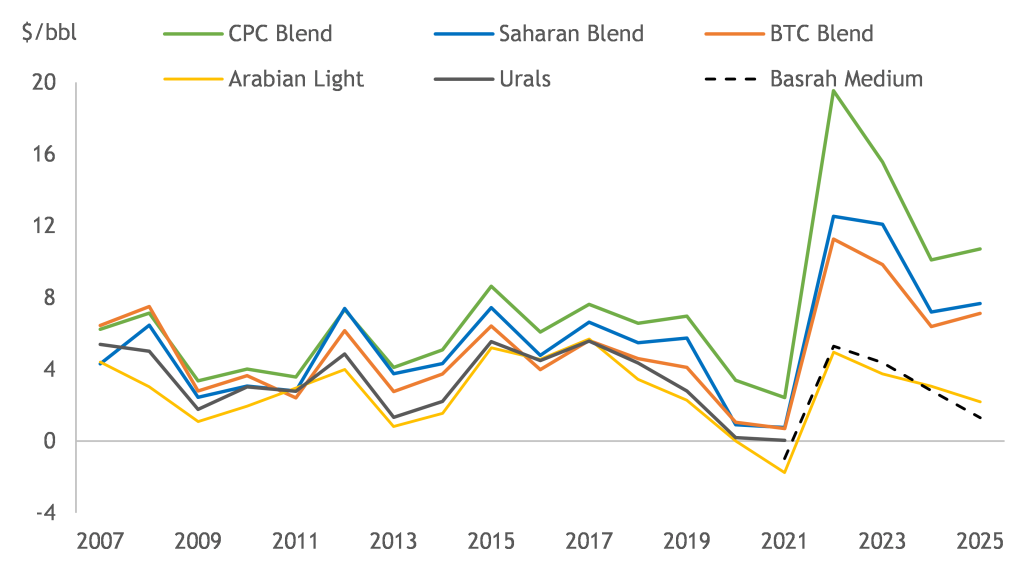

It has been the case for some time that very light crude oils in the Mediterranean offer better refining margins. This is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: FOB Med margins with different crudes

Since March 2022, Urals has no longer been available. The refining margins with BTC Blend and the other light crudes reached historical highs. BTC Blend has been offering margins that since 2022 have been on average $3.75/bbl higher than Arabian Light. Very light crudes such as Saharan Blend and CPC Blend have offered even better margins. In reality, processing crudes such as CPC Blend or Saharan Blend is even more advantageous than what is shown in the figure. This is because these crudes have a lower yield of vacuum gasoil (VGO), so after processing 1 barrel of either of these crudes, the refiner has obtained a higher margin and still has additional conversion capacity to capture other opportunities.

Crude oils derive their value from the value of the refined products that can be made from them. In theory, the price differential between any two crude oils should be the differential at which one crude can be substituted for the other while making the same margin. I will refer to this as the “parity” price. If a crude happened to be available at a lower price, then it would be more attractive. Refiners would bid up its price, forcing it back to the parity price. Written this way sounds simple and, perhaps, obvious, so why does the theory seem to work for some crudes and not for others?

Additional techno-economic considerations

Quite often, these disconnects happen because different fundamentals set price differentials. Mediterranean refineries find processing very light crudes problematic mostly for two reasons:

- They do not produce enough feed for residue conversion capacity

- They produce too much naphtha

A complex refinery would normally be expected to process a slate with enough residue to fill its conversion capacity. In doing so, it might opportunistically process a mix of light and heavy crudes, which it blends to a target average. Processing a slate that is so light to leave conversion capacity unutilized, is a large “opportunity cost” that is not built into the comparison of Figure 1. However, when too much light crude is injected into the slate, this is precisely what may happen.

The margins of Figure-1 assume that naphtha is upgraded to gasoline. However, the yield of naphtha obtained from CPC Blend and Saharan Blend exceeds the naphtha upgrading capacity of most European refineries.

These constraints limit the refining capacity that is able to realize the full value from processing these crudes. Many refineries will process them only after diluting them into a composite slate that is balanced to the refinery configuration. This requires refineries to procure heavy crude, which in the European market has been scarce for some time. Straight run fuel oil exported from Russia was typically used for this purpose, but currently this is not possible.

Export of CPC Blend has now reached 1.5 million b/d with the most recent increase of Tengiz’ production. Supply is well in excess of the capacity that exists to process them without the technical limitations that reduce their value. Prices must fall as needed to create sufficient demand to balance supply, but what is the differential at which this condition is met?

What differential supports market penetration in the Mediterranean?

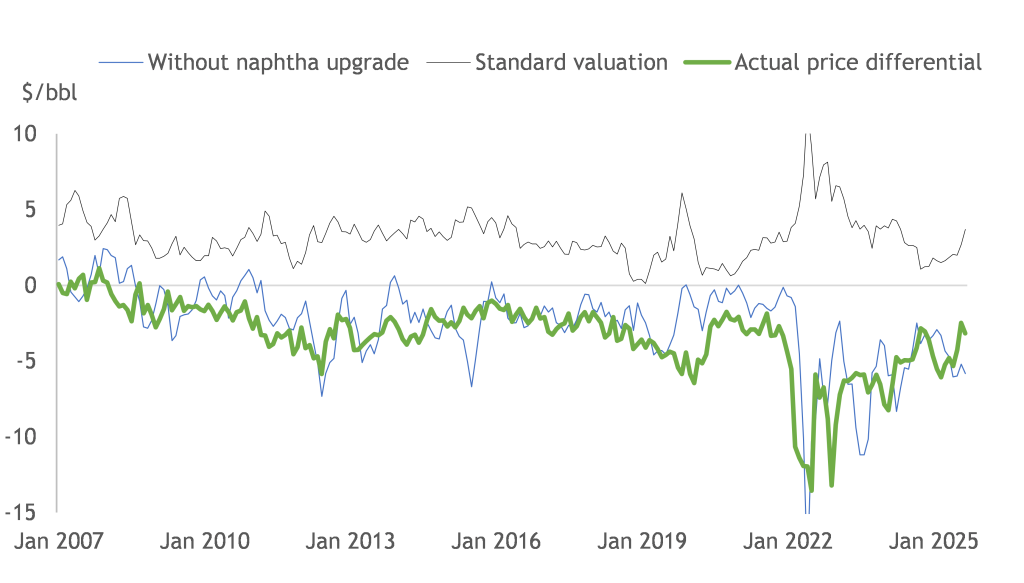

Figure-2 below shows the price differential to BTC Blend that the reference Mediterranean FCC refinery would be prepared to pay under two hypotheses:

- The standard valuation method, where the refinery processes either crude at full value with FCC yields (at constant FCC capacity).

- An alternative method, where it is assumed that when BTC Blend is substituted with CPC Blend there is no capacity to upgrade the incremental naphtha and no ability to find heavier crude to fill up the FCC.

The “discounted” valuation made with the second hypothesis explains past differentials sufficiently well over a period of many years. At this price level, the amount of refining capacity that is willing to process the crude increases substantially, so prices find a floor.

Figure 2: Back-casting the price differential between CPC Blend and BTC Blend

The gap between the two valuations has been increased by the strong reforming margins that have prevailed in the last 10-15 years. A further contribution to the gap comes from the fact FCC utilization per barrel of crude processed is lower in the alternative hypothesis.

The influence of arbitrage to Asia

Another mechanism that is triggered when price differentials drop, is arbitrage to other markets. The value of naphtha in North Europe and Asia is higher than in the Mediterranean, so the value of naphtha-rich crudes is correspondingly higher. The arbitrage of CPC Blend and to North Europe is normally open. Both crudes have been leaving the Mediterranean regularly to sail North and West. The intent here is to discuss arbitrage to Asia, which used to be sporadic but has grown in importance.

Saharan Blend can be loaded in VLCCs and shipped Round Cape, so it can be arbitraged more cost effectively to the Far East. Shipping restrictions in the Bosporus and the Suez Canal limit CPC Blend parcels to Suezmax, making arbitrage to India comparatively easier.

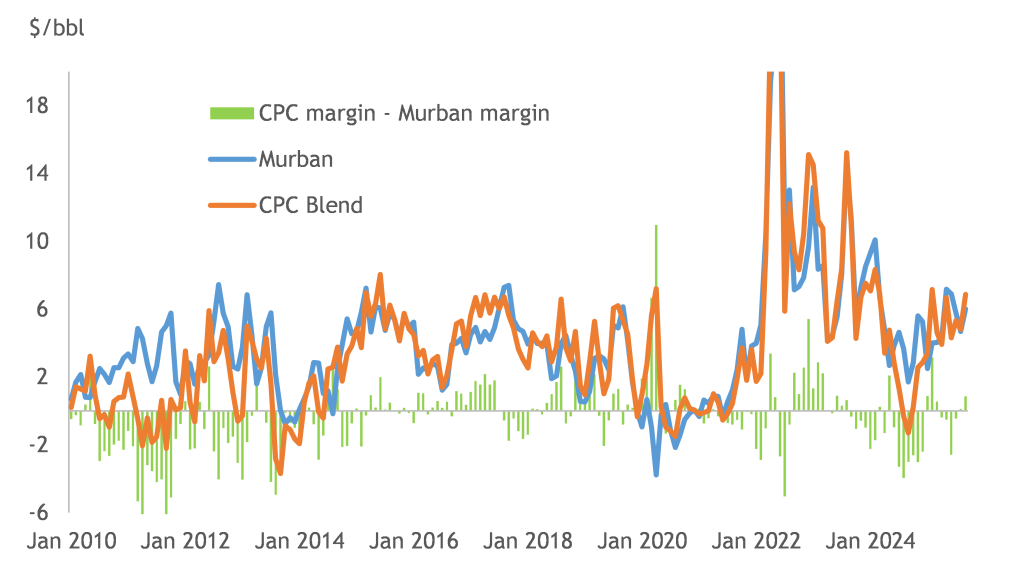

Figure 3 below compares historical CPC Blend margins and Murban margins at Singapore. It shows that before 2016 a Singapore refinery would have obtained higher margins with Murban, a 40.5oAPI Middle Eastern crude sold in the spot market. The situation started changing in 2016, after which it became quite frequent to see months when CPC Blend margins were higher.

Figure 3: CPC Blend and Murban FCC margins at Singapore

Are these margin trends reflected in the trade data?

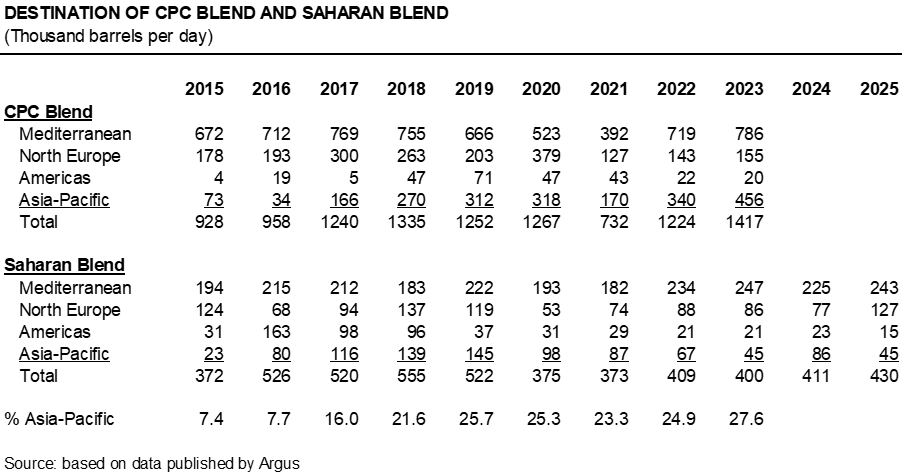

Argus Media publishes data about the destination of CPC Blend and Saharan Blend cargoes. Unfortunately, the database published by Argus does not show CPC Blend exports after May 2023, but a paper published by Vortexa1 can be used to supplement the data.

The total volume of these two crudes that has been processed in Europe has crept up slightly, despite several refinery closures. This is an indication of higher market penetration induced by favourable prices. The share of trade to Asia-Pacific grew strongly in 2017 and 2018.

According to Figure 3, CPC Blend ceased being favourable to Asian refineries in September 2023. This agrees with the Vortexa paper, which shows less trade to Asia in 2024. According to Figure 3, the arbitrage was favourable again between January 2025 and March 2025. Vortexa shows higher volumes to Asia at the beginning of 2025. This demonstrates that the value of CPC Blend in Asia makes a strong contribution to provide a floor to prices.

Figure-2 shows that between 2017 and 2022 the price differentials to BTC Blend were somewhat lower than the discounted valuation. This coincided with the period of growing trade to Asia. Therefore, it seems plausible that both mechanisms contribute to provide a floor to CPC Blend prices.

The combination of higher penetration in the Mediterranean market and arbitrage to Asia is balancing supply and demand. The recent increase of CPC Blend export after the expansion of Tengiz production is likely to increase the frequency with which the Asian market sets prices. This would continue to make the crude very attractive to Mediterranean refineries that can process it without the technical limitations discussed earlier.

© Midhurst Downstream, 2025

1 https://www.vortexa.com/insights/insights-crude-cpc-blend-at-centre-of