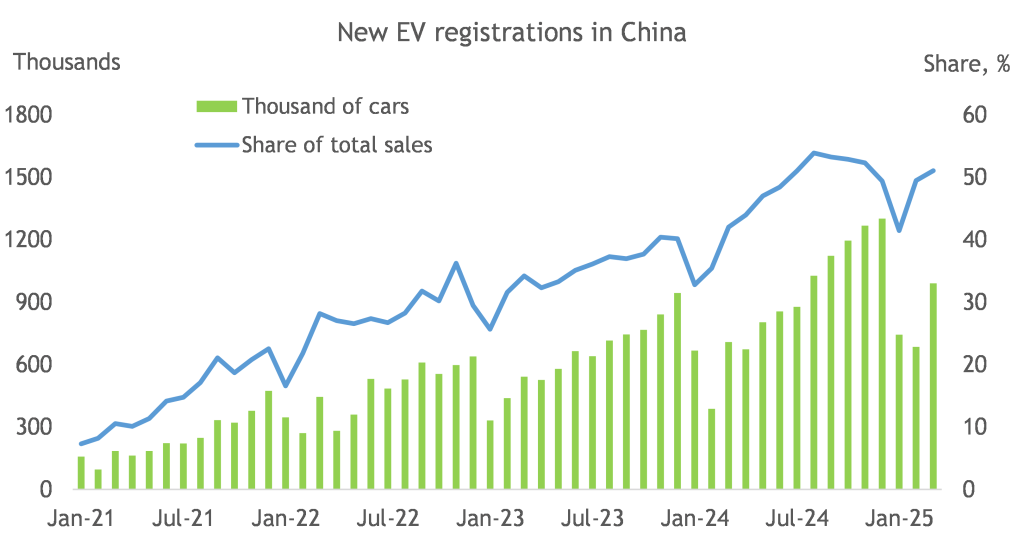

In China the share of Electric Vehicles (EV’s) on new car registrations has reached 50%. In the second half of 2024, gasoline demand was 130kbd lower than the same period in 2023. What could be the implications for global refining?

Summary

In China the share of Electric Vehicles (EVs) on new car registrations has reached 50%. In the second half of 2024, gasoline fell relative to the same period in 2023. An EV share of 50% will most likely result in a stagnation of gasoline demand, but it should not produce a rapid decline. Could this cause Chinese refineries to export more gasoline and make a negative impact on the scenario for global refining?

The Chinese refining industry operates in a regulated market. The experience of the past 15 years has shown the extent to which refineries have been able to adapt there yields to changing demand patterns, while keeping net import/export stable. It seems probable that a gradual and predictable decline of gasoline demand would cause domestic refineries to evolve and keep the impact on global refining moderate. However, another significant step forward of battery technology could cause the EV share to grow even higher, possibly with larger consequences.

Relevant statistics

The surge of popularity of Electric Vehicles in China started in 2021 and growth has been steady. The most recent data show that maybe a plateau has been reached at ~50%, but this will become clearer as more data are available for 2025. The popularity of EV’s is attributed to lower battery costs relative to Europe and to the fact that China is at the cutting edge of battery technology. An even higher proportion of two-wheel vehicles is driven by batteries.

Source: data published by China Automobile Dealers Association

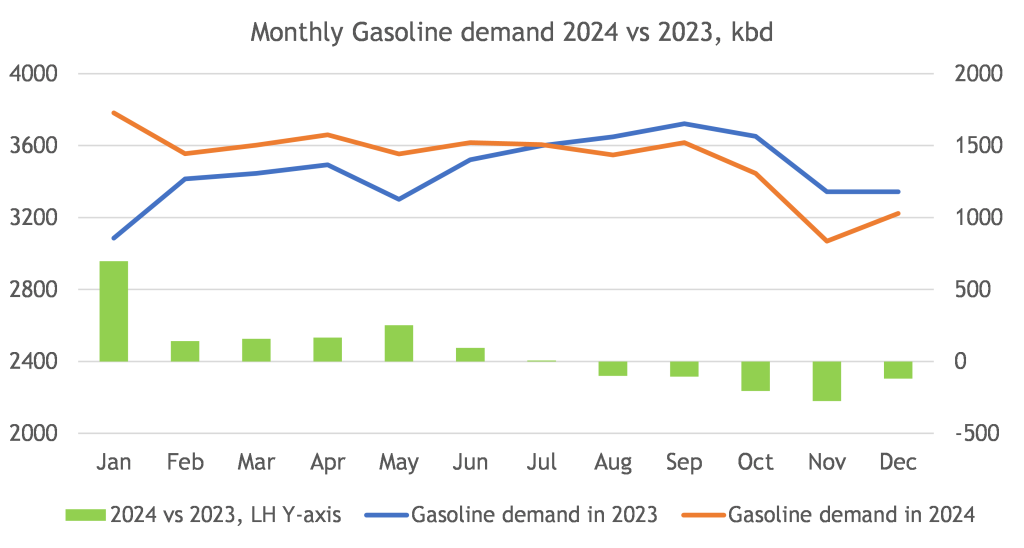

At the end of 2023, the IEA estimated the total cumulative displacement of gasoline demand by EV’s in China at 310kbd. The 2024 level of car registration would have displaced another ~200kbd of gasoline demand. For reference, the average year-on-year growth of gasoline demand in China between 2010 and 2019 was 154kbd, so a tipping point has potentially been reached. The result is that gasoline demand has started recording year-on-year declines since August 2024. In Q4 2024, gasoline demand was 200kbd lower than Q4 2023.

Looking more closely at the car population statistics, it seems that maybe lower economic activity also played a role. At the end of 2023, China had a passenger car fleet of 287 million vehicles, typically growing by between 10 and 20 million vehicles every year (the average of the last ten years has been 17 million). Registration of new cars is typically 20-21 million vehicles per year. The statistics imply that ~80% of new cars in China go to grow the fleet and only ~20% go to replace old cars. It also means that an EV share of 50% is still not sufficient to cause the fleet of ICE vehicles to decline. Hence the possibility that the deterioration of the economy made a contribution. Irrespective of this, as the fleet becomes larger and older a high market share of EV’s will eventually cause gasoline demand to decline permanently.

In 2023, EV’s were 7.6% of the fleet and should reach approximately 13% in 2025. A simple projection of recent trends, i.e. assuming further but gradual growth of the EV’s share of new registrations, shows that the fleet of ICE cars would peak around 2030, by which time the share of EV’s in the fleet will be more than 25%. Vice versa, if the EV share of new registrations stays at 50%, this would result in an ICE fleet that keeps expanding for a while longer. Either way, gasoline demand would still be affected by the improvement of fuel efficiency. In the first scenario, gasoline demand is at peak. In the second scenario it is probably at a plateau, but will eventually start declining.

Possible impact on global markets

The concern for global refining is the extent to which China may increase gasoline export, depress Singapore prices and affect international margins negatively.

It is possible to make a comparison with Europe. When European gasoline demand started falling because of the sudden increase of diesel cars popularity from the late 1990’s, strong refining margins supported refining throughput until 2008. The reduction of European gasoline demand produced a corresponding increase of net export, mostly to the US East Coast. When the recession arrived in 2009 and margins crashed, initially there were more refinery closures in the US East Coast than in Europe. Could China develop so much gasoline overcapacity to trigger a similar chain of events?

It is less likely for two reasons. One is that the total car fleet in China is still expanding, so it will take more than 50% EV market share to cause a rapid reduction of gasoline demand. The other one is that Chinese refineries do not operate in a free market and would probably be made to adapt to a gradual and predictable reduction of gasoline demand.

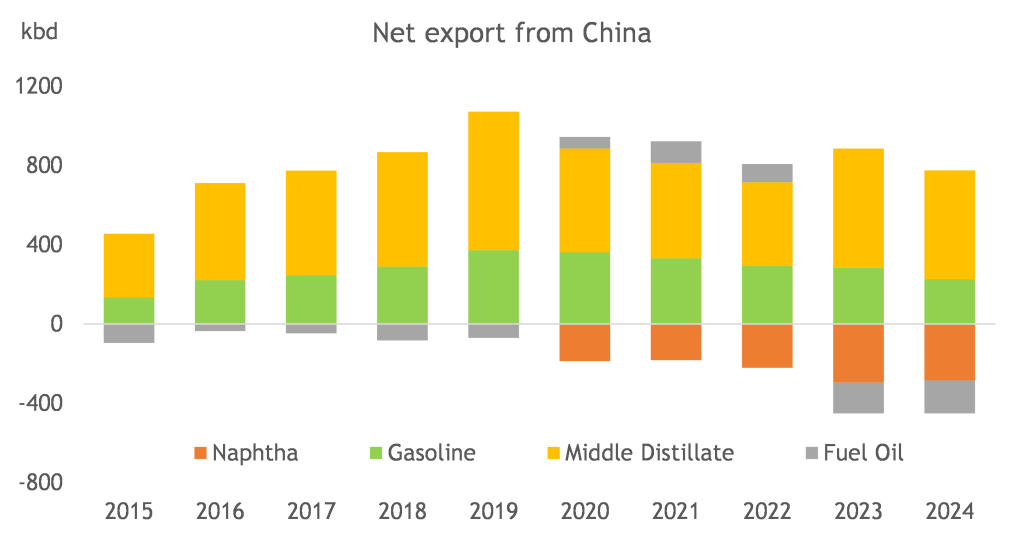

In China, import of crude and export of products are subject to quotas. Recent history shows the extent to which this can cause Chinese refineries to disconnect from global fundamentals. In late 2021, the government was preparing for the end of the lock-downs and cut product export quotas to ensure supply to the domestic market in 2022. In reality the lock-downs continued until the end of 2002, domestic demand grew very little and refinery throughput remained chocked. Despite low domestic demand, tight global markets and very strong refining margins internationally, Chinese export remained low until September 2022. In late 2022, the government finally increased export quotas to allow refineries to profit from high export margins. Export of light transportation fuels was at a multi-year minimum of 400kbd in June 2022 and quadrupled to 1.6 million barrels per day in December 2022.

As long as export is managed this way, refineries will seek to adapt their yields to domestic demand. The impact of China on the global market would mostly be via the level of import or export that will come to exist because of regulation.

Net export of light transportation fuels from China peaked at 1.1 million b/d in 2019 and is currently ~800kbd. Even though 2021 and 2022 saw large mid-year changes of policy, annual average volumes have been quite stable, considering the amount of investment that has gone in the Chinese refineries, the wild swing of demand and margins that have occurred recently and the extent to which product demand has changed since 2015.

Refining capacity has been developed to adapt to demand. Several refineries of recent construction have high yields of petrochemicals and a yield of fuels below 50%. In many cases, they crack atmospheric gasoil to make naphtha for aromatics. The middle distillate yield of Chinese refineries was 42 vol% in 2011 and has reduced to 34 vol% in 2024. In fact, China currently exports more kerosene than gasoil (or diesel). Meanwhile, the yield of naphtha has increased from ~7 vol% to ~13 vol%. With a refining throughput of 15.5 million b/d, a swing of 8 vol% from middle distillates to petrochemicals feed has removed from the market ~1.2 million b/d of middle distillate.

This illustrates how Chinese refineries have adapted to strong growth of petrochemicals demand at home, while gasoil/diesel demand was stagnating. If the same demand patterns had been witnessed in a market economy, margin maximization would have been the main consideration driving refinery strategies. More refineries would have chosen to produce higher value middle distillate, while purchasing naphtha from the market. By now, China would be a large importer of naphtha and a large exporter of gasoil/diesel, much like South Korea. But in China the outcome has been different and refineries have tracked domestic demand through the construction of several large “crude-to-chemicals” refineries that crack gasoil to naphtha for petrochemicals.

While gasoil/diesel demand was stagnating, which means it was falling as a percent of the domestic demand barrel, gasoline demand was growing in absolute terms and remained fairly constant as a percent of total demand until 2021. Only recently, gasoline demand has started reducing as a percent of total demand. Thus, as Chinese refineries were adding capacity designed to convert middle distillates to petrochemicals, the country average yield of gasoline remained quite constant at 24-25 vol%.

Would China in future become a larger exporter of gasoline? If the reduction of gasoline demand will be gradual and predictable, such an outcome seems unlikely. Shifting refinery yields from gasoline to petrochemicals is easier than it was for gasoil/diesel. There is no cracking involved in the process. Refineries would start re-configuring by using more straight run naphtha or reformate for petrochemicals.

By contrast, a rapid unexpected decline of gasoline demand would force the government to allow more export of gasoline, because the alternative would be lower refinery throughput and, potentially, a shortage of many other products.

At present, the first of these two scenarios still seems the more probable, but there is quite a lot going on in the development of battery technology that could bring some surprises.

Another pertinent observation is that other countries in Asia have started developing EVs supply chains. These include India, Vietnam and Indonesia, which are very important to future growth of oil demand, and where EV’s have reached ~10% of new vehicle registrations.

Last updated in April 2025

© Midhurst Downstream, 2025