Refining margins have returned to normal levels and closures have resumed in Europe. However, not all is bad for European refining. There are also some factors of competitive advantage to support good refineries. The middle distillate market is structurally in deficit and cause prices to be higher relative to other regions. High freight costs are sustaining European margins. Despite the loss of Russian crude supply, crude oil prices have remained lower than in Asia. Supply of light crude continues to be abundant and to offer opportunities, especially in the Mediterranean.

Competitive positioning of European refining relative to Asia

The European refining industry is certainly in a phase of transition. I am not referring to the energy transition, the impact of which is mostly in the future, but to the transition from the very high margin environment in 2022-24 to the current environment of lower, although still respectable margins. PetroIneos has announced the closure of Grangemouth and Shell will stop processing crude at Wesseling. BP is planning to reduce crude capacity at Gelsenkirchen. Prax, having acquired the Lindsey refinery not too long ago, has filed for bankruptcy.

The discourse has shifted very quickly from the astronomical margins of 2022-24 to refinery closures. As usual, it is assumed that Europe will be the region with the most closures, but I think the story is somewhat more complicated. There are undoubtedly factors that weigh against the competitiveness of European refining, but also factors that suggests good European refineries should be able to compete.

Amongst the negatives, it is the near certainty that Europe will continue to have a surplus of gasoline even with the closures. In the medium term, gasoline demand is quite strong because Electric Vehicles are mostly replacing diesel cars and, for a substantial part, we will be replacing diesel cars with gasoline-hybrid. However, gasoline demand will eventually resume declining and it is difficult to see how the global market can absorb a volume of gasoline export from Europe higher than what is already doing. The Dangote refinery seems to be finally reaching its full capacity after a very long period of commissioning. Therefore, the European refining industry will eventually be forced to reduce gasoline production and this will be a factor in setting the amount of refining capacity to be removed.

Once European refining capacity has adapted to the size of the accessible gasoline market, the reminder of the European refineries will benefit from two key factors of competitive advantage:

- They operate in a market that is structurally short of middle distillate.

- The cost of crude in the Atlantic region is lower than in the Pacific region.

Before Russia invaded Ukraine, European refineries used to benefit from Russian crude available at prices that were lower than the price of crude of equivalent quality in the Arabian Gulf. This is no longer the case, which has penalized mostly North Europe, but Mediterranean refineries continue to benefit from abundant supply of light crudes at low prices.

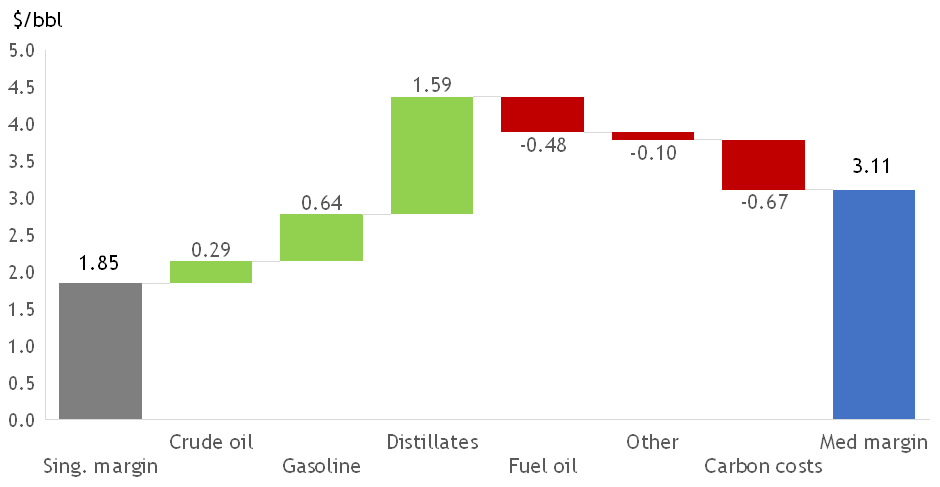

These two factors create a price scenario with refining margins FOB Med that are higher than FOB Singapore. Figure 1 makes a comparison at constant yields and 2024 annual average prices. The benchmark is a medium complexity refinery that processes Arabian Light with a mild hydrocracker and FCC. At FOB Singapore prices, this refinery has a variable margin of $1.85/bbl. An equivalent Mediterranean refinery would pay $0.29/bbl less for crude (hence adding $0.29/bbl to the margin), sell light products at a higher price (+$2.23/bbl) and fuel oil at a lower price (-$0.48/bbl). After paying $0.67/bbl of carbon costs, the Mediterranean refinery still has a margin that is $1.26/bbl higher. Without carbon costs, the difference would have been $1.93/bbl. High carbon costs are a threat for European refineries, because a possible reduction of free allocations in 2026 and/or a tightening of the carbon market, could push them above $1.00/bbl.

Figure 1: Bridge between FOB Med and FOB Singapore variable margin at 2024 prices

Source: proprietary models

Some of the factors that are to the advantage of European refineries are structural and unlikely to go away. They stem from the fact the European market is short of middle distillate, whereas the Asian market is short of crude and fuel oil. The value of the European advantage on middle distillate prices has been inflated by high freight costs, so it is reasonable to expect it will reduce in a lower freight rate environment. However, it is a fact that renewed tensions in the Middle East hindering trade via Hormuz and the Red Sea have caused European margins to go up in July/August 2025, whereas Singapore margins reduced. By contrast, the European advantage on gasoline prices is fairly precarious in the long term and cannot be taken for granted. In this case, the tensions in the Middle East hinder access to any opportunities that may open up via Suez.

The opportunity offered by very light crudes

The comparison uses Arabian Light because it is sold in both markets at prices that are specific to each market. Therefore, it allows making a comparison at constant yields. However, it does not capture what is a real opportunity available to Mediterranean refineries, i.e. to enhance margins by processing lighter crudes.

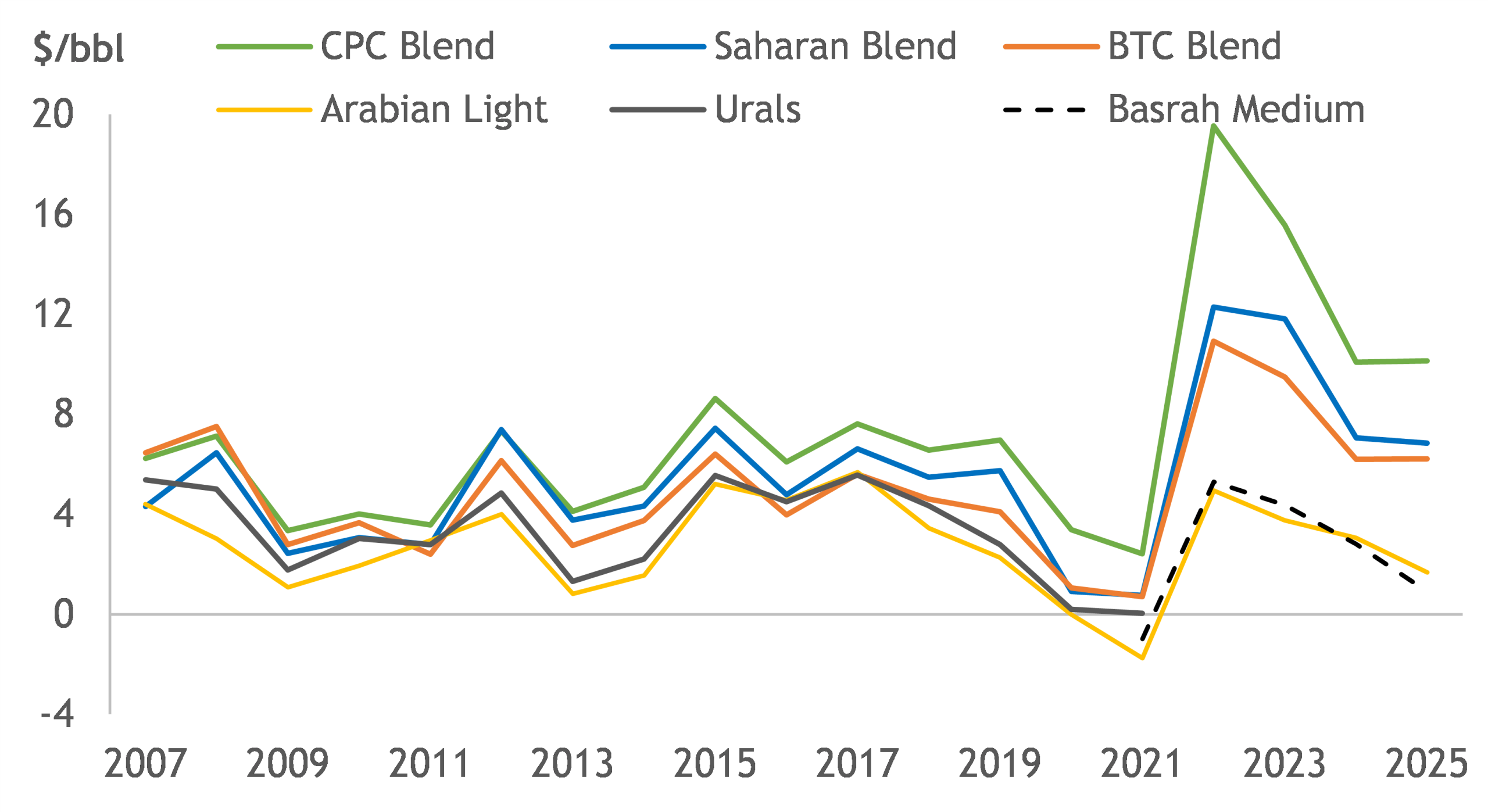

Figure 2 below shows the margins of the same refinery with six different crudes. CPC Blend and Saharan Blend are very light. BTC Blend is also a light crude. The other ones are heavier and have a higher content of sulphur. Until 2019, Arabian Light, Urals and BTC Blend were priced to compete with one another, which is evident from the fact they used to offer similar margins.

Figure 2: FOB Med margins with different crudes

Since March 2022, Urals has no longer been available. The refining margins with BTC Blend and the other light crudes reached historical highs. The same would have been seen with WTI, which is now processed regularly in Europe and is part of the Brent complex. However, Arabian Light and Basrah Medium, which are sold under term agreements and from a quality standpoint are possible replacements for Urals, did not follow the light crudes. The result is that BTC Blend has been offering margins that since 2022 have been on average $3.75/bbl higher than Arabian Light. Very light crudes such as Saharan Blend and CPC Blend have offered even better margins.

In order to make the comparison between the Mediterranean and the Singapore benchmark completely fair, we need to observe that opportunities to beat the Arabian Light benchmark exist also in Asia. Abundance of light crude has been a global trend in the last 10 years or so. In Asia, there were several refinery upgrades and new refineries designed to process medium/heavy crude. Therefore, the price scenario in Asia is such that complex refineries bid up the prices of scarce heavier crudes, while simpler refineries obtain better margins with lighter crudes. As an example, the margin with Murban is currently ~$4/bbl higher than with Arabian Light. The margin with Arabian Extra Light is also $1-2/bbl higher than with Arabian Light.

Let’s focus on the Mediterranean market now to explore the reasons for the apparently advantageous prices of very light crudes.

What explains the prices of these crudes?

One consideration to make is that processing crudes such as CPC Blend or Saharan Blend is even more advantageous than shown in Figure 2. This is because these crudes have a lower yield of vacuum gasoil (VGO), so after processing 1 barrel of either of these crudes, the refiner has obtained a higher margin and still has some additional conversion capacity that can be utilized to capture other opportunities.

The companies that market these crudes are presumably able to make the same analyses I am making here and come to the conclusions that these crudes may be sold at higher prices. Hence the question of what explains their prices. I believe, it is mostly two factors:

- These crudes do not produce enough feed for residue conversion capacity.

- They produce too much naphtha.

A residue conversion refinery, for example one with a coker or a residue hydrocracker, would normally be expected to process a slate that is heavy enough to fill its residue conversion capacity. In doing so, it might opportunistically process a mix of lighter and heavier crudes, which it blends to a target average. Processing a slate that is so light to leave conversion capacity unutilized is a very large “opportunity cost” that is not built into the comparison of Figure 2.

However, when too much light crude is injected in the slate, there is a point specific to every refinery beyond which it becomes very difficult to find enough heavy crude to counter balance. In the European market, there has been a relative scarcity of heavy crude for some time, so atmospheric residue exported from Russia would typically be used for the purpose. Currently, this is no longer possible, so it has become more difficult for refineries to process very light crude while simultaneously filling up their conversion capacity.

The refining margins of Figure-2 assume that naphtha is upgraded to gasoline. However, crudes like CPC Blend and Saharan Blend have a yield of naphtha that exceeds the isomerization and reforming capacity installed at the majority of the European refineries. The high yield of naphtha can be a problem also for the crude distillation units, which are rarely designed for the heat and mass balance that is needed to process these crudes. The weighted average reforming capacity in the Mediterranean is 13vol% of distillation capacity, whereas very light crudes have a yield of naphtha higher than 20vol%.

The consequence of the above is that the majority of refineries can process these crudes only in cocktails with other crudes and needs to dilute them into a slate with distillation yields that are balanced to the process capacities installed downstream of the crude distillation units. This would not have much of an impact on market prices if these crudes happened to be produced in small volumes. The problem is that export of CPC Blend reached 1.3 million b/d with the start up of the Kashagan field and has now reached 1.5 million b/d with the further increase of Tengiz’ production. The combined export of Saharan Blend, CPC Blend, plus other very light North African crudes is equivalent to about 30% of the refining capacity that receives crude via import terminals in the Mediterranean or the Black Sea.

While this market situation was being created, several refineries with low complexity were closed in Europe. These were the type of refineries with the highest incentive to process light crudes. Some others were upgraded with the addition of cokers and residue hydrocrackers.

If Figure-2 had shown coking margins, the curves would have been much closer to one another. This is because lighter crudes use less coking capacity, so their valuation benefits less from assuming that the residue would be converted. The same would have happened if margins had been calculated making the assumption that naphtha is not upgraded to gasoline. This means that when the prices of these crudes fall to levels that compensate for the loss of coking margin or for the loss of reforming margin, they become attractive for a wider population of refineries and additional demand for them is created.

Another mechanism that is triggered when the prices of these crudes slide too much is arbitrage to North Europe or Asia. In both of these markets, the price of naphtha is higher than in the Mediterranean and so is the value of naphtha-rich crudes, once delivered. CPC Blend and Saharan Blend feature in the crude slates of refineries in North Europe and are arbitraged to Asia.

The fact that the prices of light crudes are below their technical values make them a good opportunity. Any amount that refineries can dilute in a composite slate and process without incurring the dis-optimizations mentioned above, will enhance margins. This market situation has existed ever since the CPC pipeline started operations, but the gap between technical value and market price has widened in recent years. As long as prices fall to the level that makes arbitrage to Asia possible or even necessary, European refiners, and Mediterranean ones in particular, are certain to find an opportunity in these crudes. In the last 23 years it has been difficult to see an end to this situation and it remains difficult to see it currently.

© Midhurst Downstream, 2025

This paper is an updated version of one originally published by RIE on the 13th of June 2025.

Stato della raffinazione Europea, complessità delle raffinerie e mercato dei greggi